Have you been affected by swimmer’s itch? Head to www.swimmersitch.ca to report your infection and support freshwater research in Alberta!

Background

What is swimmer’s itch?

Swimmer’s itch (also known as duck itch, lake itch, or cercarial dermatitis), is a temporary skin rash that some people develop after swimming in water infested with microscopic parasites called schistosomes. These parasites normally live in the bloodstream of certain birds and mammals, as well as in the bodies of some species of water snails. Infected snails will release a free-swimming larval form of the parasite into the water, and if they come into contact with a swimmer, they will try to burrow into that person’s skin. Fortunately, humans are not suitable hosts for the parasite and the larvae die shortly after penetrating the outer layer of skin. This causes an allergic reaction to occur which leads to the formation of an itchy bump. Swimmer’s itch is found throughout the world, in both freshwater and salt water, and is more frequent during the summer months.

Although uncomfortable, swimmer’s itch is not considered dangerous and is usually short lived- the reaction typically clears up on its own within a week or two. In the meantime, you can control the itching with over-the-counter or prescription medication.

How does the water become infested with these parasites?

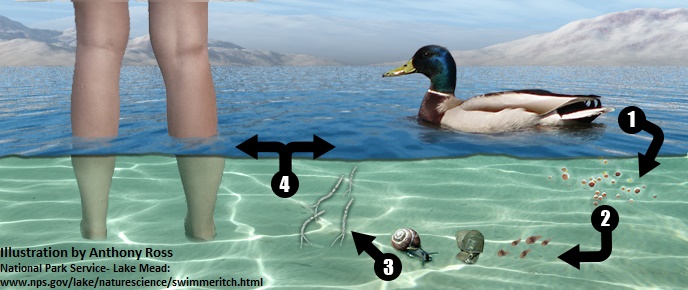

The adult parasite lives in the blood of infected birds such as geese, ducks, gulls, swans, and certain mammals like muskrats and raccoons. The adult parasite will produce eggs that are then passed in the feces of the infected birds or mammals (1).

If the eggs land in or are washed into the water, the eggs will hatch, releasing small, free-swimming larvae called miracidia (2). These larvae swim in the water in search of certain species of aquatic snails.

If the miracidia find one of these snails, they will infect the snail, multiply, and undergo further development. Under optimal conditions, infected snails will then release a different type of microscopic larvae, known as cercariae (3), into the water. These free-swimming larvae will then search out a bird or mammal host to infect in order to complete their lifecycle (4).

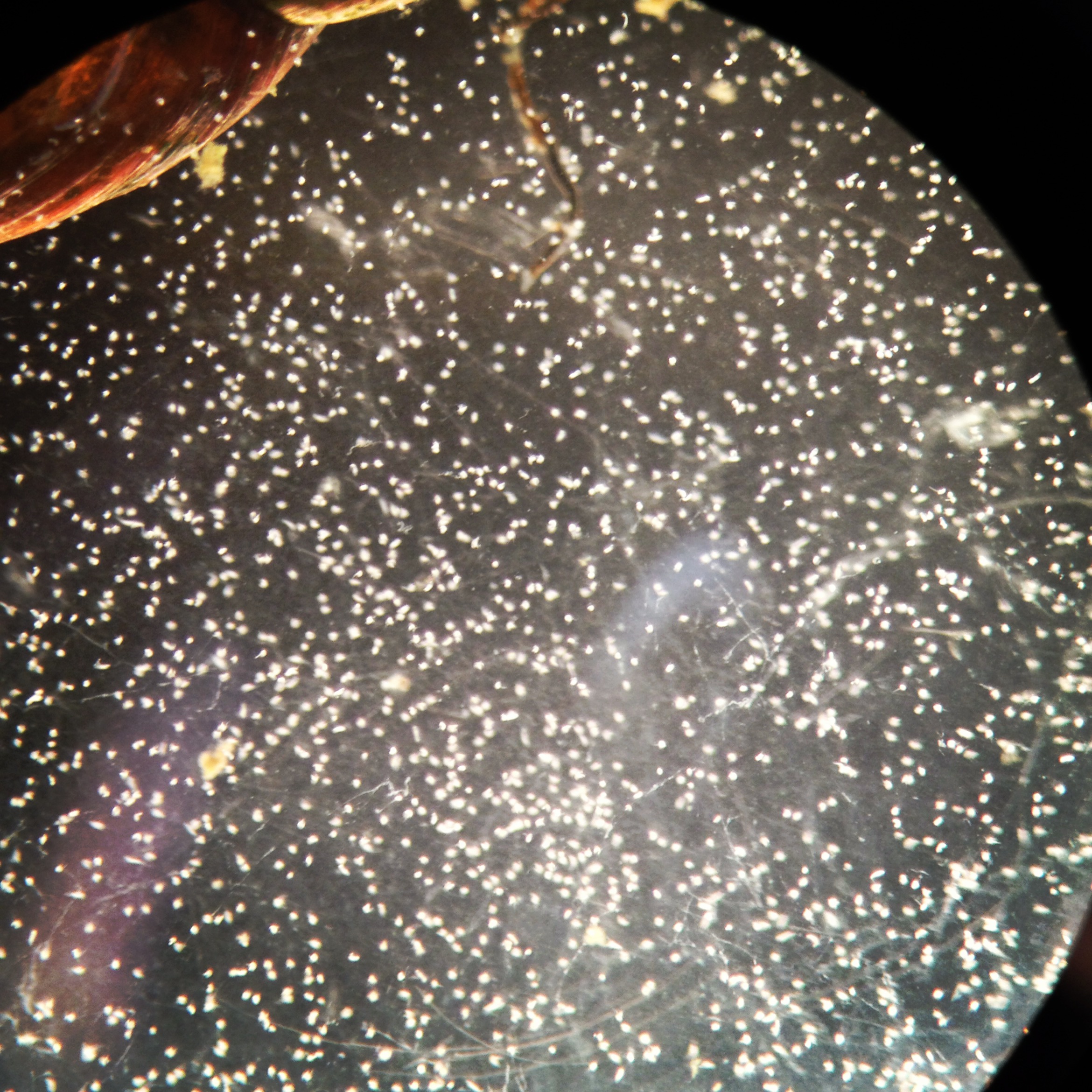

magnified image of a cercariae under the microscope

Swimmer’s itch occurs when these cercariae encounter a human (4), and accidentally penetrate the human skin instead of their natural hosts such as waterfowl and aquatic mammals. Because humans are not a proper host, the parasites cannot develop, and quickly die. This results in an allergic reaction and the development of an itchy rash on the skin.

When and where are these parasites found?

The parasites responsible for swimmer’s itch can be found in many lakes, ponds, and reservoirs throughout Alberta. Most cases are usually reported during the warm summer months (i.e. June-September) when beach use is at its heaviest. The highest incidence of infection appears to be late in the day, after a period of sustained wind.

The larvae are most likely to be present in shallow water near the shoreline and close to aquatic vegetation (i.e. the same areas snails are often found). The larvae tend to concentrate near the surface of the water where they have the greatest chance of coming into contact with birds and mammals.

Note: Wind can push the tiny parasites to all edges of the lake, often some distance from the snails the larvae came from.

Health effects associated with swimmer’s itch

What are the Symptoms?

Symptoms can range from mild skin irritation to a severe, itchy red rash depending on how sensitive an individual is to the parasites and how many larvae actually get into the skin. The reaction, which looks like reddish pimples or blisters, may appear on exposed skin (i.e. skin not covered by a swimsuit, wetsuit, etc.) within minutes to days after swimming or wading in infested water.

Typically, as you begin to dry off and the larvae start to burrow into the skin, you may notice a tingling sensation develop on exposed parts of the body. Small, pin sized red spots/pimples will then develop within 12 hours anywhere the larvae have penetrated the skin. Eventually, the tingling sensation disappears, and the red spots enlarge, resulting in small itchy blisters, similar to an insect bite. This may form a larger, itchy rash which can persist for days to weeks, but should clear up on its own. Although it might be difficult, it is important not to scratch the itchy area too much as this may result in secondary bacterial infections.

The degree of discomfort will vary for each person depending on the sensitivity of the individual to the parasite, the severity of the infestation, and prior exposure. Because swimmer’s itch is caused by an allergic reaction to the parasites, the more often you swim or wade in infested water, the more intense and immediate the symptoms will be.

Important Note: Be aware that swimmer’s itch is not the only rash that may occur after swimming in fresh or salt water.

See: cyanobacteria (blue-green algae)

How long do the symptoms last?

Since the larvae die shortly after entering the skin, the infection is considered self-limiting, lasting on average 2 to 5 days. However, the symptoms associated with infection (i.e. the burning or itchy feeling) can persist for up to 2 weeks.

Who is at risk of getting swimmer’s itch?

Anyone who swims or wades in infested water may be at risk of getting swimmer’s itch, and the more time you spend in that water, the higher your risk becomes.

Children are usually more affected by swimmer’s itch than adults. This is because children tend to have more sensitive skin, are more likely to swim and play in areas with high concentrations of larvae (i.e. shallow water, close to the shore), and are less likely to dry themselves off with a towel immediately after leaving the water.

Children are usually more affected by swimmer’s itch than adults. This is because children tend to have more sensitive skin, are more likely to swim and play in areas with high concentrations of larvae (i.e. shallow water, close to the shore), and are less likely to dry themselves off with a towel immediately after leaving the water.

Is swimmer’s itch dangerous?

No. The rash and itch are mostly just irritating, especially for younger children. Normally there is no serious risk of danger associated with infection because the parasite cannot enter the blood and the rash does not spread from the initial points of contact with the larvae. The infection is also self-limiting, which means it will usually clear up on its own in time.

It should be noted, however, that there is a risk of developing a secondary bacterial infection in the skin. Scratching the area too much may result in the rash becoming infected; if this occurs, you should contact your health care provider right away.

Call your doctor if you still have the rash after two weeks or if you have signs of infection, such as:

- Increased pain, swelling, warmth, or redness

- Red streaks leading from the area

- Pus draining from the area

- A fever

Can swimmer’s itch be spread from person-to-person?

No. Swimmer’s itch is not contagious which means it cannot be spread from one person to another.

What can I do if a rash develops?

There are a number of non-prescription options you can take at home, which may reduce some of the itchiness associated with swimmer’s itch. Common treatments include:

- Applying anti-itch lotion (e.g. Calamine lotion) on the affected area; these can be purchased without a prescription from your local grocery or drugstore, and help to sooth some of the itch.

- Applying a cool compress on the affected skin

- Taking shallow, lukewarm baths, with 3 tablespoons of baking soda added to the water or applying a baking soda paste to the rash (which is made by stirring water into baking soda until it reaches a paste like consistency)

- Bathe in Epsom salts

- Soak in colloidal oatmeal baths

- Taking antihistamines

Remember to avoid scratching as much as possible, as this may cause the rash to become infected. If itching is severe, your health care provider may suggest prescription strength lotions or creams to lessen the symptoms.

Call your doctor if you still have a rash after two weeks or if you have signs of a bacterial skin infection.

Recreational Water Use

Once an outbreak of swimmer’s itch has occurred in the water, will the lake always be unsafe?

No. Many factors must be present for swimmer’s itch to become a problem in water. Since these factors can change over time (sometimes within one season), swimmer’s itch will not always be a problem. However, there is no way to know how long water will be unsafe. Larvae generally survive 24 hours in the water once released from the snail, and an infected snail will continue to shed cercariae throughout the remainder of its life. For future snails to become infected, migratory birds or mammals in the area must also be infected so the lifecycle can continue.

Is it safe to swim in an outdoor swimming pool?

Yes. As long as the swimming pool is well maintained and chlorinated, there is no risk of swimmer’s itch. The appropriate snails must be present for swimmers itch to occur.

Prevention

How can I avoid swimmer’s itch?

Unfortunately, there is no sure way to avoid swimmer’s itch entirely, unless you avoid lakes, ponds, and beaches all together. There is however certain precautions you can take to reduce the risk, including:

- Avoiding areas known to be infested:

- Speak with other visitors in the area, local health officials, or parks representatives about water conditions before going into the water.

- You can also check for warning signs at public beaches, lakes and picnic areas, however, not all beaches will have signage for swimmer’s itch. Or check online, there are various websites including swimmersitch.ca which posts recent reports of swimmer’s itch for various lakes across Canada

- Avoid areas with dense aquatic vegetation, as this is where snails are most likely to be found

- Try to enter the water from a dock or boat, rather than wading in from the beach, since the larvae tend to concentrate near the shoreline.

- Toweling down:

- Drying yourself off with a towel as soon as you come out of the water may remove the parasites before they can penetrate the skin.

- Showering:

- Taking a shower immediately after leaving the water will not remove any larvae that have already burrowed into the skin, but it may limit the severity of the infection by washing away any parasites still on the surface.

- Applying waterproof sunscreen:

- It has been suggested that applying waterproof sunscreen before entering the water may help to reduce the number of larvae that penetrate the skin.

Can Swimmer’s itch be controlled at the Source?

It was commonly believed that chemical treatment of snail populations would break the life cycle of the parasite associated with swimmer’s itch. However, such actions can result in ecological damage and are generally not permitted in public water. Furthermore, swimmer’s itch is caused by the free swimming larval stage, which can be blown or carried many hundreds of meters, perhaps kilometers, from the snail source, which makes chemical control of limited value.

Where to get more information on swimmer’s itch:

https://myhealth.alberta.ca/health/Pages/conditions.aspx?hwid=abl0355

- This site provides a brief overview of the health risks associated with swimmer’s itch.

- This site provides information about what swimmer’s itch is and where it has been found in Canada. There is also a section where you can report your itch.

https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/swimmersitch/

- This site describes in detail what causes swimmer’s itch and answers common questions relating to the health effects of swimmer’s itch.

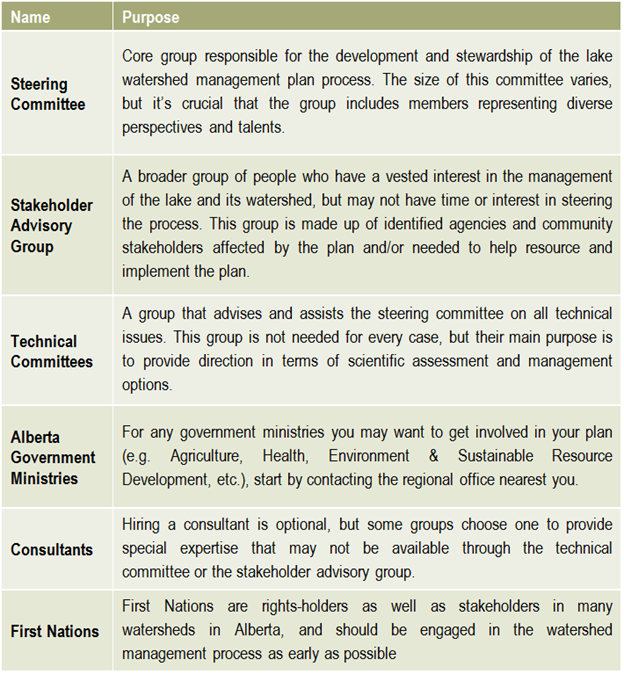

The members of the steering committee will continue to play a strong role in facilitating and tracking implementation actions. This includes any actions they were responsible for, as well as tracking other committees and sector’s actions and progress made towards achieving the plan’s outcomes. Ongoing communication is essential to successful implementation and achieving outcomes, therefore a regular reporting mechanism could be set up in order to provide regular evaluation of the plan.

The members of the steering committee will continue to play a strong role in facilitating and tracking implementation actions. This includes any actions they were responsible for, as well as tracking other committees and sector’s actions and progress made towards achieving the plan’s outcomes. Ongoing communication is essential to successful implementation and achieving outcomes, therefore a regular reporting mechanism could be set up in order to provide regular evaluation of the plan.

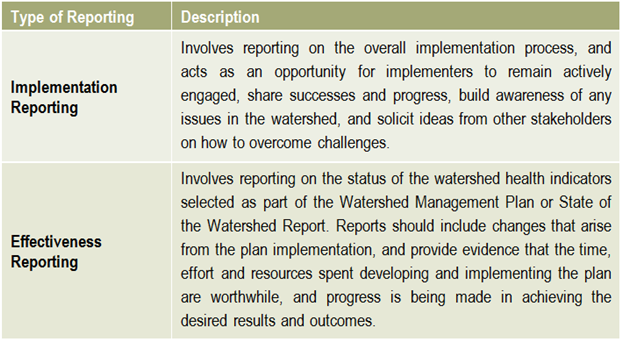

Reporting is an essential component of any watershed management planning and implementation process. There are two main types of reporting that should be shared with stakeholders on a regular basis: implementation reporting & effectiveness reporting.

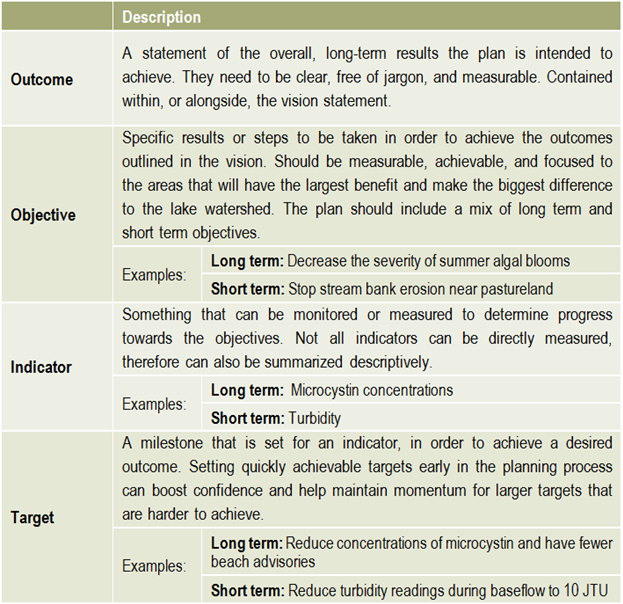

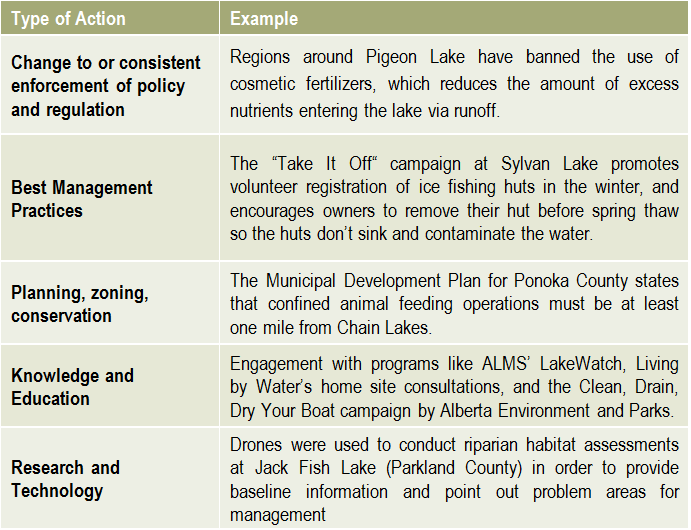

Reporting is an essential component of any watershed management planning and implementation process. There are two main types of reporting that should be shared with stakeholders on a regular basis: implementation reporting & effectiveness reporting. There is no limit to the number or types of lake management actions, but they typically fall into the categories on the right.

There is no limit to the number or types of lake management actions, but they typically fall into the categories on the right.

Helpful resources

Helpful resources The development of a lake watershed management plan provides the guidance needed to implement activities, but the plan cannot be static. Monitoring the performance of your management actions is essential to understanding whether your goals have been met, and whether further actions are needed. Monitoring and evaluating the implementation and effectiveness of a lake watershed management plan allows assessment of progress towards the goals and objectives of the plan, identification of problems and opportunities, and a collection of critical information required when performing a 5 or 10 year review of the plan.

The development of a lake watershed management plan provides the guidance needed to implement activities, but the plan cannot be static. Monitoring the performance of your management actions is essential to understanding whether your goals have been met, and whether further actions are needed. Monitoring and evaluating the implementation and effectiveness of a lake watershed management plan allows assessment of progress towards the goals and objectives of the plan, identification of problems and opportunities, and a collection of critical information required when performing a 5 or 10 year review of the plan.

What has the monitoring results of the plan and of the indicators shown? Is there a need to modify the plan? It is important that the lake watershed management plan does not just sit on a shelf. Information gaps should be addressed, action items need to be managed, completed, and evaluated to best address the needs of the lake. Always keep in mind the vision: if the actions taken are not bringing the lake closer to that vision, then the plan needs to be modified. Consider updating both the state of the watershed and the lake watershed management plans at regular intervals to make sure that the actions taken were achieving the desired outcomes and to evaluate what work still needs to be done.

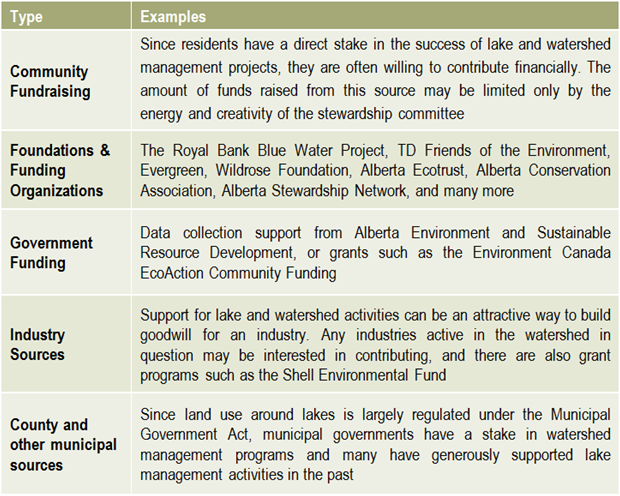

What has the monitoring results of the plan and of the indicators shown? Is there a need to modify the plan? It is important that the lake watershed management plan does not just sit on a shelf. Information gaps should be addressed, action items need to be managed, completed, and evaluated to best address the needs of the lake. Always keep in mind the vision: if the actions taken are not bringing the lake closer to that vision, then the plan needs to be modified. Consider updating both the state of the watershed and the lake watershed management plans at regular intervals to make sure that the actions taken were achieving the desired outcomes and to evaluate what work still needs to be done. Once a plan has been approved by all affected sectors and officially endorsed and released by the steering committee, then implementation can begin in full. Action projects can be large and comprehensive, or made smaller by staging projects over time or into modules that can be tackled one at a time. Fundraising is an issue that many community groups may find intimidating, but experience with programs such as the Pine Lake Restoration Program (see

Once a plan has been approved by all affected sectors and officially endorsed and released by the steering committee, then implementation can begin in full. Action projects can be large and comprehensive, or made smaller by staging projects over time or into modules that can be tackled one at a time. Fundraising is an issue that many community groups may find intimidating, but experience with programs such as the Pine Lake Restoration Program (see  This graphic describes how the various committees and groups will work and interact together. The circle size depicts the approximate number of people involved, and the circles overlapping indicates that some individuals may reside in all of the circles and participate in multiple committees as part of the planning process. The technical committee is shown as an arrow, indicating that it is independent and has relatively few people, and yet it interacts with all of the groups. This graphic may look different depending on the lake and the people involved, and a detailed structure should be agreed upon and described in the plan’s Terms of Reference (Step 6).

This graphic describes how the various committees and groups will work and interact together. The circle size depicts the approximate number of people involved, and the circles overlapping indicates that some individuals may reside in all of the circles and participate in multiple committees as part of the planning process. The technical committee is shown as an arrow, indicating that it is independent and has relatively few people, and yet it interacts with all of the groups. This graphic may look different depending on the lake and the people involved, and a detailed structure should be agreed upon and described in the plan’s Terms of Reference (Step 6).