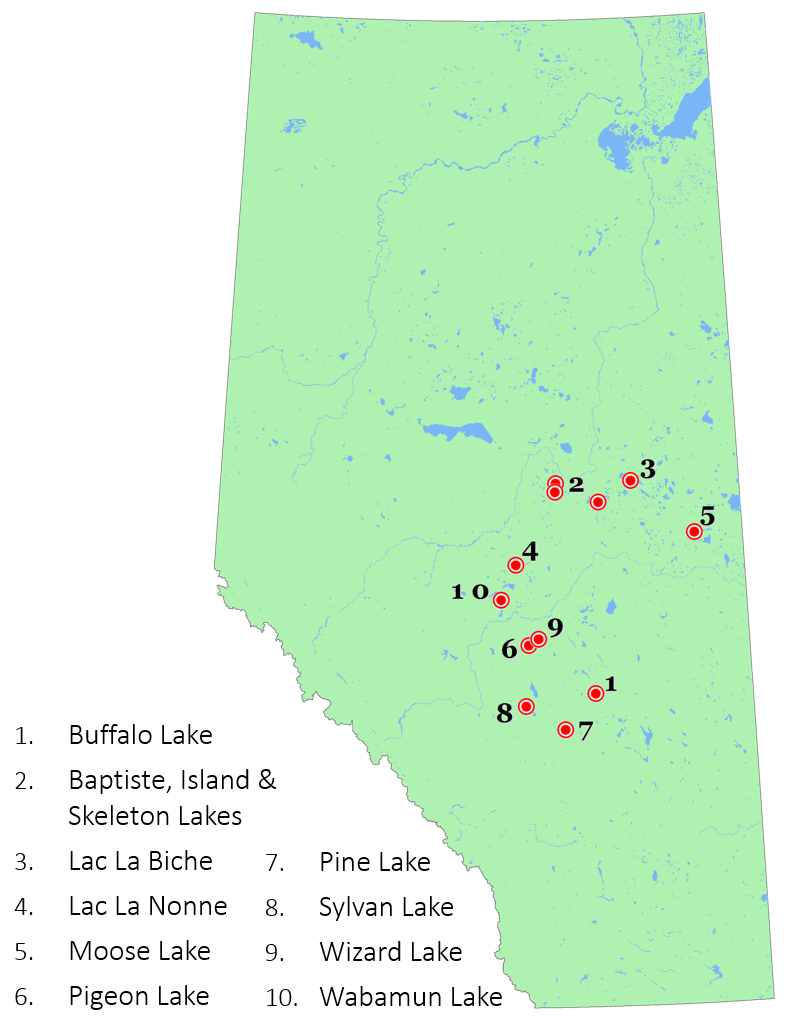

There are many case studies included in ALMS’ Workbook for Developing Lake Watershed Management Plans in Alberta. These case studies are listed below, sorted by lake and which section of the management plan process they relate to. To jump to a specific case study, click on the text in the map legend or on the number in the map.

Please note: As of now, the interactive map doesn’t work well on mobile devices. Sorry for any inconvenience! You can scroll down to read the case studies, or download the whole workbook PDF here.

Buffalo Lake

3.3 Municipal Planning & Bylaws – Intermunicipal Development Planning (pg. 16)

Buffalo Lake is a unique situation in Alberta where the lakewater levels are controlled and a shoreline right-of-way is owned by the Provincial government. An Integrated Shoreland Management Plan for Buffalo Lake (BLISMP) was approved in 2009. Shortly after, in 2010, an Inter-municipal Development Plan (IDP) was developed by the five municipalities surrounding the lake to address issues on private land adjacent to the right-of-way. This IDP provides direction on land-use, appropriate activities, and development on private lands around the lake. It supports and complements the policy direction outlined in the BLISMP. It is a good example of how a centralized plan could be used to deal with development pressures around a lake surrounded by multiple municipalities. Go to www.blmt.ca or visit the websites of involved municipalities (Lacombe, Stettler, and Camrose Counties or the Summer Villages of Rochon Sands or White Sands).

Baptiste, Island and Skeleton Lakes

4.1 Develop an initial vision (pg. 21)

LakeWatch Sampling at Baptiste Lake – 2013

Summer villages at Baptiste, Island, and Skeleton Lakes have formed the Baptiste, Island and Skeleton Lakes Watershed Management and Lake Stewardship Council (BISL). BISL’s vision for Baptiste Lake is to “maintain a healthy lake and watershed, recognizing the importance of living within the capacity of the natural environment and providing sustainable recreational, residential, agricultural, and industrial benefits”.

The Baptiste and Island Lake Stewardship Society

State of the Baptiste Lake Watershed Report (2008)

Lac La Biche

3.3 Municipal Planning & Bylaws – Wetlands and Riparian Areas (pg. 15)

Lac La Biche County included provisions for riparian protection in their Municipal Development Plan and in their Lakeshore Policy and Environmental Reserve Environment Policy. Riparian setback distances were calculated using scientific methods resulting in site-specific and defensible riparian development setbacks to prevent pollution entering the county’s lakes. These setbacks ranged in distance, depending on the site, reaching a maximum distance of 50 m from the lakeshore.

View the Lac La Biche County Municipal Development Plan here.

Lac La Nonne

6.1 Identify and Prioritize Issues and Opportunities Through Stakeholder Engagement (pg. 37)

In 2003 a survey was conducted at Lac La Nonne (Watershed Edge Resource Group 2004) in response to concerns over water quality and lake health. The survey was geared to watershed stewardship and was sent to 1400 landowners and 251 were returned. The majority of the respondents felt that water quality had deteriorated with time, 31% said water quality was poor, 51% said very poor. When asked to rank conditions or activities perceived to impact watershed health the results were:

- Low water level

- Application of agricultural fertilizers and/or other chemicals

- Livestock grazing and manure management

- Cottage septic/wastewater systems

- Application of lawn fertilizers/chemicals

- Upstream on farm/private/municipal drainage

- Annual agricultural cropping practices

- Water allocations or withdrawals

- Lakeshore cottage/beach development

- Clearing of riparian and shoreline areas

- Removal of aquatic or lakeshore vegetation

- Local oil and gas activity

- Erosion/sedimentation/runoff

- Recreational activities (boating, swimming, others)

- Others (including road construction, high volume public traffic, inflow/outflow obstructions)

The Lac La Nonne Enhancement Protection Association (LEPA) Website

Moose Lake

6.6 Drafting and Confirming Support for the Plan (pg. 46)

In 2006, after two years of collaboration, the Moose Lake Watershed Society released its Moose Lake Watershed Management Plan (MLWMP). It has five main objectives:

- Improve wildlife & fish habitat,

- Improve riparian health & wetland management,

- Increase public awareness & land stewardship,

- Improve water quality within the watershed,

- Incorporate the Lake Management Plan into municipal planning documents.

To achieve objective one group decided to work to protect a key fish spawning habitat on the west side of the lake. The society undertook extensive planning (mapping) and stewardship (garbage clean-up, trail maintenance) activities in order to convince the provincial government to designate 13 sections of Crown land in part provincial park and park provincial recreation area. The combination of park types was to serve the dual purposes of protecting the natural and recreational resources of the area. The society hosted extensive public consultations, and got support from the surrounding municipalities prior to submitting a proposal to the provincial government.

Objective five has been critical to achieving many of the other objectives; the M.D. of Bonnyville has used the MLWMP as a guideline for several municipal initiatives. The document has been taken as a general management plan and implemented county wide using both regulatory and non-regulatory projects to achieve the five objectives.

In 2007 they created and began enforcing a Municipal Lands Bylaw, which includes the protection of the Environmental Reserves, as well as a Private Sewage Disposal Bylaw which establishes a process for assessing septic failure and potential threats to the lakes. They partner with other municipalities and organizations to control invasive, and dangerous plant species including Himalayan Balsam and Water Hemlock in riparian areas.

Education is key to many of the objectives as well. The M.D. of Bonnyville posts information signs on all environmental reserves surrounding lakes and on tributaries flowing to Moose Lake. Shoreline health sessions are offered by the M.D. to educate landowners. Each year Grade 5 classrooms take a field trip to Moose Lake to learn about lakes and their watershed as part of the Walking with Moose program.

*Note: Moose Lake has not experienced increases in phosphorus concentrations or decrease in clarity based on long-term monitoring records (Casey 2011).

Pigeon Lake

3.3 Municipal Planning & Bylaws – Agriculture (pg. 16)

Wetaskiwin County’s Municipal Development Plan excludes confined feeding operations (CFOs) from the area within one mile of Pigeon Lake. It further describes an additional area, contiguous to and beyond the exclusion zone, within which CFOs are allowed but are subject to “very strict requirements regarding run-off”. These requirements are developed by the County in co-operation with the Natural Resources Conservation Board (NRCB).

5.3 Establish the Structure Under Which Participants Will Contribute (Pg. 35)

The Pigeon Lake Watershed Association (PLWA) appointed a steering committee to provide recommendations on the development and implementation of their Watershed Management Plan (WMP). The Steering Committee includes representatives from Alberta Agriculture and Rural Development, Alberta Environment and Sustainable Resource Development, the Association of Pigeon Lake Municipalities that includes all summer villages and the Counties of Leduc and Wetaskiwin, Battle River Watershed Alliance, PLWA and ALMS. Committee members were also asked to identify other stakeholder groups to participate on the Steering Committee.

The Pigeon Lake Watershed Association (PLWA) appointed a steering committee to provide recommendations on the development and implementation of their Watershed Management Plan (WMP). The Steering Committee includes representatives from Alberta Agriculture and Rural Development, Alberta Environment and Sustainable Resource Development, the Association of Pigeon Lake Municipalities that includes all summer villages and the Counties of Leduc and Wetaskiwin, Battle River Watershed Alliance, PLWA and ALMS. Committee members were also asked to identify other stakeholder groups to participate on the Steering Committee.

They intend to implement their watershed management plan in a number of phases, over a period of years. The committee that should be involved in a specific stage of the process is shown in brackets:

- Engaging the public and stakeholder advisory group for input into the plan (steering committee).

- Identifying critical areas in need of management and identifying management tools and techniques (technical sub-committee).

- Development and endorsement of a draft WMP and an implementation plan by stakeholders (steering committee & stakeholder advisory group).

- Implementation by stakeholders of mitigation measures agreed to (stakeholder advisory group).

- Ongoing monitoring, reporting, review and evaluation of plan implementation and progress (steering committee).

6.3 Develop an Engagement Strategy (Pg. 40)

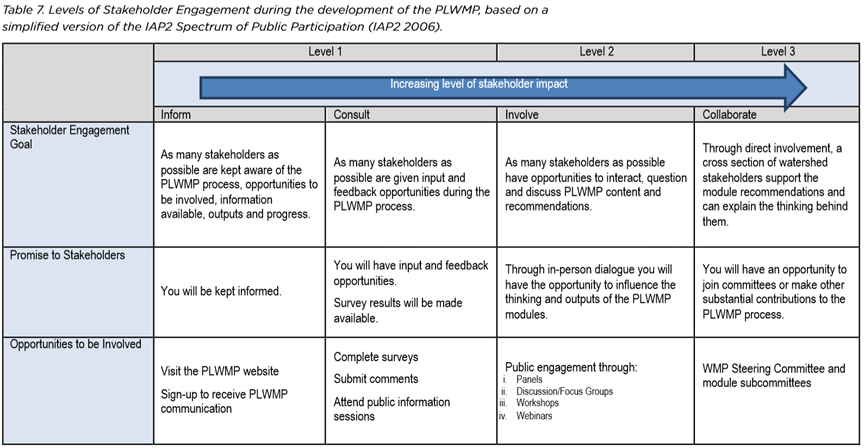

The Pigeon Lake Watershed Management Plan used the principles of the International Association of Public Participation (IAP2) to inform their engagement strategy. They planned that the level and type of engagement will vary at different points during the lake watershed management planning process. Stakeholders can determine the degree to which they would like to be involved in the development of the Pigeon Lake Watershed Management Plan. The table below (from page 40) describes levels of engagement for the PLWMP which was based on a simplified version of the IAP2 Spectrum of Public Participation (iap2canada.ca).

Pine Lake

7.3 Implementing the Plan (Pg. 49)

Pine Lake – September 2011

Pine Lake is a small intermittently-stratified, eutrophic lake (surface area = 3.98 km²; mean depth = 5.3 m) southeast of Red Deer. Pine Lake was subject to severe cyanobacterial blooms. Public concern over deteriorating water quality prompted the Alberta government to initiate a lake restoration program in 1991.

Alberta Environment conducted a detailed diagnostic of the lake and a phosphorus budget was developed. The Pine Lake Restoration Society, an organization with representatives from the farming, commercial, resort, and cottage communities, implemented a four-year work plan of watershed projects and in-lake treatment that addressed nutrient loading from all sources in 1995. Then, watershed projects were developed at critical areas in the watershed to reduce external phosphorus loading. To remove internal loading (phosphorus released from lake sediments), a hypolimnetic withdrawal system was installed in 1998, and later a treatment wetland was installed downstream of the hypolimnetic discharge creek. A monitoring program was implemented to assess the benefits of the watershed projects and hypolimnetic withdrawal system in 1999 and initial results are summarized in this report and within LakeWatch Reports.

The program has resulted in tangible improvements in lake water quality. Total dissolved phosphorus levels have decreased in Pine Lake since the hypolimnetic withdrawal system began operation in 1999. Dissolved oxygen concentrations have improved in winter. In 2000 alone, chlorophyll-a approached the goal of the restoration program, a natural level of algal productivity. But the program cannot be considered a complete success, because nuisance algal blooms continue to occur after wet periods. Also, there was insufficient water to operate the system during a drought in two of the seven years since 1999, and water levels sometimes fell below target elevations. Larger weights have been added to the sections of the hypolimnetic withdrawal pipeline that lost weights and floated. Results to date provide no evidence of significant adverse impacts of hypolimnetic discharge on water quality in Ghostpine Creek.

This was the first program of its type in Alberta, the most extensive, and has served as a model for other Alberta communities since. The Restoration Society is still in operation, continues to monitor water quality, and are considering further lake and watershed projects designed to reduce phosphorus to an even lower level.

Learn more about the Pine Lake Restoration Society on their website.

Sylvan Lake

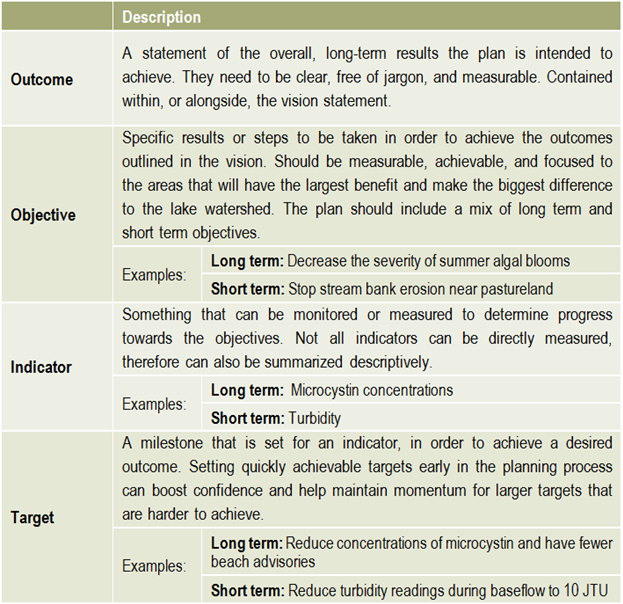

6.4 Identifying Outcomes, Objectives, and Indicators (Pg. 41)

Sylvan Lake – 2014

The Sylvan Lake Watershed Management Plan Committee, comprised of representatives from municipal governments surrounding the lake, hosted a workshop to engage Sylvan Lake Watershed stakeholders in their vision and desired outcomes for the watershed. They asked “In 2020, in an ideal future, Sylvan Lake is/has…” and came away with an extensive list of desired outcomes. The outcomes were ranked, shortlisted, and a few prioritized for the focus of the watershed management plan. The outcomes were:

- Environmentally Healthy Lake and Watershed

- Planned Diverse Recreation

- Collaborative Planning

Their vision: Sylvan Lake and its watershed are a healthy, treasured resource where a responsible, collaborative planning approach achieves a balance between development, nature, and recreation.

6.4 Identifying Outcomes, Objectives, and Indicators (Pg. 43)

Sylvan Lake Management Committee, when developing their Cumulative Effects System for the lake, developed a formal process of reporting and vetting plan outcomes, indicators, and thresholds at each stage in the planning process. This ensured that the respective municipalities had adequate time to comment and to understand the plan recommendations.

Wizard Lake

4.2 State of the Watershed Reporting (Pg. 22)

Owing to its proximity to Edmonton, the lake’s sheltered situation, and the recreational opportunities it offers, Wizard Lake is one of the busiest small recreational lakes in central Alberta. In the past, several lake management plans were created for the lake but none provided for integrated management across the whole watershed. The Wizard Lake Watershed and Lake Stewardship Association recognized that this failure was due to lack of a cohesive body of information on the lake. They prioritized a State of the Watershed Report to summarize all currently available watershed information and then lead into the development of an integrated watershed management plan that aligns with the Water for Life strategy and current regulations.

Owing to its proximity to Edmonton, the lake’s sheltered situation, and the recreational opportunities it offers, Wizard Lake is one of the busiest small recreational lakes in central Alberta. In the past, several lake management plans were created for the lake but none provided for integrated management across the whole watershed. The Wizard Lake Watershed and Lake Stewardship Association recognized that this failure was due to lack of a cohesive body of information on the lake. They prioritized a State of the Watershed Report to summarize all currently available watershed information and then lead into the development of an integrated watershed management plan that aligns with the Water for Life strategy and current regulations.

Wabamun Lake

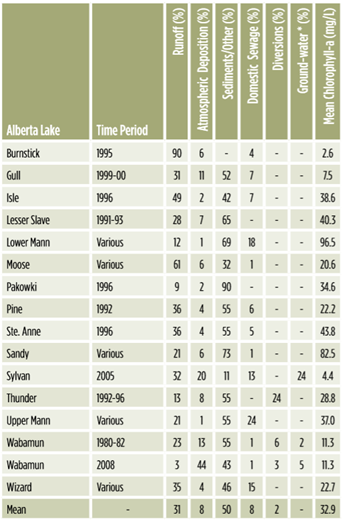

4.3 Additional Techinical Studies – Nutrient Budgets (Pg. 27)

Phosphorus concentrations for runoff, precipitation and lake water were measured at Wabamun Lake during the 2008 open water season and used in conjunction with extensive historical data at the lake to produce a representative water and total phosphorus budget (AENV 2011).

- Lake sediments (43%)

- Precipitation falling directly onto the lake surface (44%)

- 2008 (dry year) runoff (3%)

- Industrial return flow (3%)

- Groundwater (5%)

- Domestic sewage (1%)

Further, in the table on the right, see how Wabamun Lake phosphorus budgets compares to other lakes in Alberta as well as the high variation between wet and dry years.

The members of the steering committee will continue to play a strong role in facilitating and tracking implementation actions. This includes any actions they were responsible for, as well as tracking other committees and sector’s actions and progress made towards achieving the plan’s outcomes. Ongoing communication is essential to successful implementation and achieving outcomes, therefore a regular reporting mechanism could be set up in order to provide regular evaluation of the plan.

The members of the steering committee will continue to play a strong role in facilitating and tracking implementation actions. This includes any actions they were responsible for, as well as tracking other committees and sector’s actions and progress made towards achieving the plan’s outcomes. Ongoing communication is essential to successful implementation and achieving outcomes, therefore a regular reporting mechanism could be set up in order to provide regular evaluation of the plan.

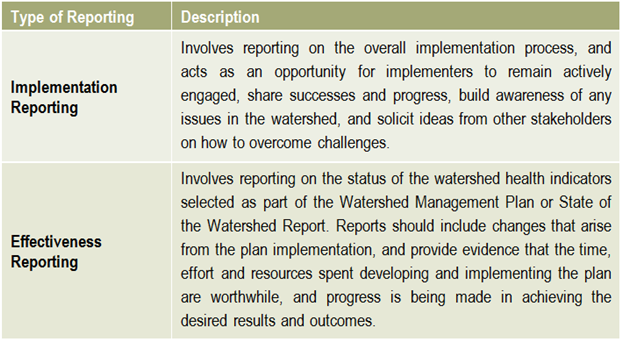

Reporting is an essential component of any watershed management planning and implementation process. There are two main types of reporting that should be shared with stakeholders on a regular basis: implementation reporting & effectiveness reporting.

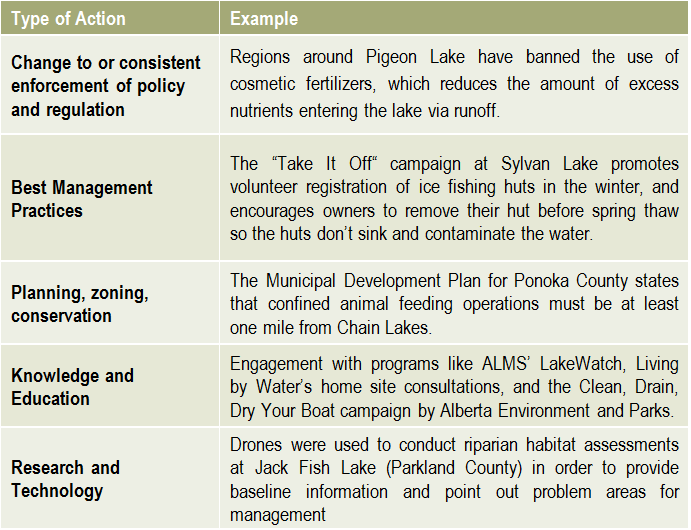

Reporting is an essential component of any watershed management planning and implementation process. There are two main types of reporting that should be shared with stakeholders on a regular basis: implementation reporting & effectiveness reporting. There is no limit to the number or types of lake management actions, but they typically fall into the categories on the right.

There is no limit to the number or types of lake management actions, but they typically fall into the categories on the right.

Helpful resources

Helpful resources The development of a lake watershed management plan provides the guidance needed to implement activities, but the plan cannot be static. Monitoring the performance of your management actions is essential to understanding whether your goals have been met, and whether further actions are needed. Monitoring and evaluating the implementation and effectiveness of a lake watershed management plan allows assessment of progress towards the goals and objectives of the plan, identification of problems and opportunities, and a collection of critical information required when performing a 5 or 10 year review of the plan.

The development of a lake watershed management plan provides the guidance needed to implement activities, but the plan cannot be static. Monitoring the performance of your management actions is essential to understanding whether your goals have been met, and whether further actions are needed. Monitoring and evaluating the implementation and effectiveness of a lake watershed management plan allows assessment of progress towards the goals and objectives of the plan, identification of problems and opportunities, and a collection of critical information required when performing a 5 or 10 year review of the plan.

What has the monitoring results of the plan and of the indicators shown? Is there a need to modify the plan? It is important that the lake watershed management plan does not just sit on a shelf. Information gaps should be addressed, action items need to be managed, completed, and evaluated to best address the needs of the lake. Always keep in mind the vision: if the actions taken are not bringing the lake closer to that vision, then the plan needs to be modified. Consider updating both the state of the watershed and the lake watershed management plans at regular intervals to make sure that the actions taken were achieving the desired outcomes and to evaluate what work still needs to be done.

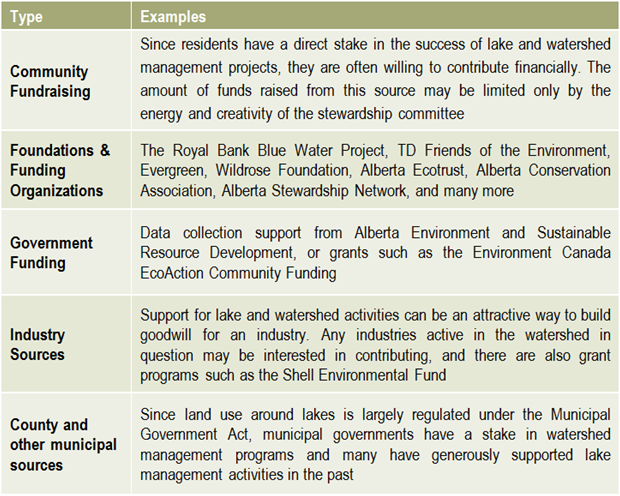

What has the monitoring results of the plan and of the indicators shown? Is there a need to modify the plan? It is important that the lake watershed management plan does not just sit on a shelf. Information gaps should be addressed, action items need to be managed, completed, and evaluated to best address the needs of the lake. Always keep in mind the vision: if the actions taken are not bringing the lake closer to that vision, then the plan needs to be modified. Consider updating both the state of the watershed and the lake watershed management plans at regular intervals to make sure that the actions taken were achieving the desired outcomes and to evaluate what work still needs to be done. Once a plan has been approved by all affected sectors and officially endorsed and released by the steering committee, then implementation can begin in full. Action projects can be large and comprehensive, or made smaller by staging projects over time or into modules that can be tackled one at a time. Fundraising is an issue that many community groups may find intimidating, but experience with programs such as the Pine Lake Restoration Program (see

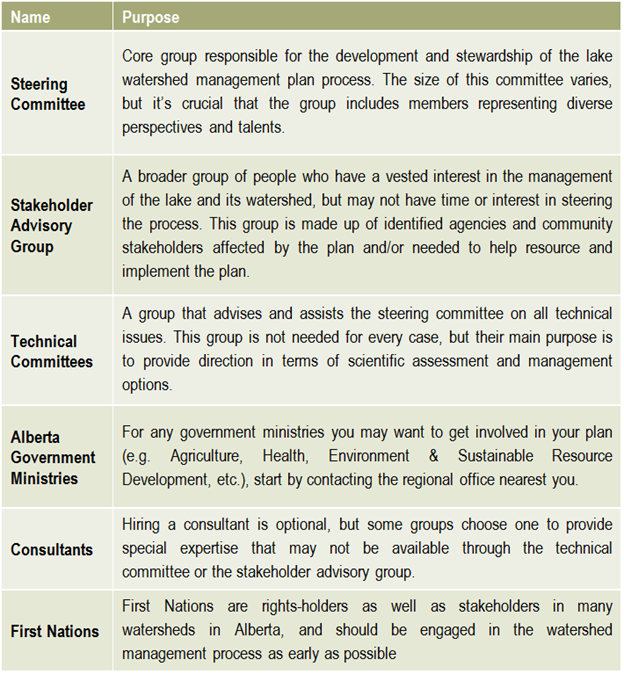

Once a plan has been approved by all affected sectors and officially endorsed and released by the steering committee, then implementation can begin in full. Action projects can be large and comprehensive, or made smaller by staging projects over time or into modules that can be tackled one at a time. Fundraising is an issue that many community groups may find intimidating, but experience with programs such as the Pine Lake Restoration Program (see  This graphic describes how the various committees and groups will work and interact together. The circle size depicts the approximate number of people involved, and the circles overlapping indicates that some individuals may reside in all of the circles and participate in multiple committees as part of the planning process. The technical committee is shown as an arrow, indicating that it is independent and has relatively few people, and yet it interacts with all of the groups. This graphic may look different depending on the lake and the people involved, and a detailed structure should be agreed upon and described in the plan’s Terms of Reference (Step 6).

This graphic describes how the various committees and groups will work and interact together. The circle size depicts the approximate number of people involved, and the circles overlapping indicates that some individuals may reside in all of the circles and participate in multiple committees as part of the planning process. The technical committee is shown as an arrow, indicating that it is independent and has relatively few people, and yet it interacts with all of the groups. This graphic may look different depending on the lake and the people involved, and a detailed structure should be agreed upon and described in the plan’s Terms of Reference (Step 6).